The Art of Storytelling in Exhibitions

Author: Tim Willis

Last Updated: April 2019

We are storytelling creatures. Whether by the light of a campfire or the glow of a computer screen, it is in telling and listening to stories that we come alive.

However, many museum and art exhibitions fail to make this powerful connection with visitors. Exhibits convey information, but they should do so much more.

Our challenge should be to provoke and inspire, to get our visitors thinking and hope that they leave our exhibitions just a little bit changed.

Our inspiration is Freeman Tilden. In many ways, his book, Interpreting Our Heritage, is as relevant today as it was when he wrote it in 1957. His ideas are brought to light again within this Art of Storytelling tool.

Our goal is to go further than just presenting information. As Freeman Tilden said, our challenge is:

“To reveal… something of the beauty and wonder, the inspiration and meaning that lie behind what the visitor can perceive.”

For those of us working in institutions both small and large, the art of storytelling in exhibitions can be a challenge.

This tool seeks to inspire you to create exhibits that do more than just present information. Our hope is that it will help you on your path to great storytelling in your exhibitions.

Acknowledgements and Special Thanks to Members of BCMA’s Small Museums Toolbox Working Group:

Elizabeth Hunter, Eric Holdijk, Joelle Hodgins, Kira Westby, Lindsay Foreman, Lorraine Bell, Netanja Waddell, Ron Ulrich, Wendy Smylitopoulos

The B.C. Museums Association gratefully acknowledges funding support of this project

The Toolkit is also available on our website below. Please see the PDF for complete content.

Contents

Overview

When we create stories, it is important to think about the person to whom we are telling them. Too often the visitor’s needs and wants become invisible to the exhibition team as they wrestle with the challenge of simply finishing the exhibit on time.

Before you embark on any exhibit, three questions should be at the forefront of your mind:

• Who are our visitors?

• What do they want?

• How do they behave?

Whatever the stated mission at your museum, art gallery, historic place or cultural centre, your mission must also include: R-E-S-P-E-C-T for your visitors.

We (workers and volunteers in the museum) are not in charge of the visitor’s experience – the visitors are.

Exhibitions are environments that visitors explore on their own terms.

Visitors have made an effort to visit our museum. They have invested time, energy and often money to get there.

When they step through your door they have an expectation: to experience something special, outside of their everyday life.

Our obligation is to treat them well, to answer their questions, to reveal new things. To do that, we must learn to tell stories well.

We can learn about creating exploratory environments from places other than museums, such as Biblo Toyen (below), a youth library in Norway.

Photo credit: aatvos / Marco Heyda.

Thinking about Visitors

Who are your Visitors

Much is written about museum visitors, their needs and learning styles. Essentially, what we need to remember is this:

Each visitor is different.

• Each visitor is interested in different things.

• Each visitor is influenced by their distinct culture and background.

• Each visitor is intelligent in their own unique way.

• When visitors come into our museums they are affected by a variety of factors – personal, social and physical – and respond in different ways.

A wonderful and thought-provoking read is the work of Harvard professor, Howard Gardner, on The Nature of Intelligence. (1)

Gardner’s theory is that each of us is more or less intelligent in different ways. These intelligences are things we are born with or that are cultivated as we grow and mature. Some of us are musically-intelligent, others find mathematics is their thing. In all, Gardner has identified nine different forms of intelligence. Bernice McCarthy, a learning theorist (2) proposes that there are four types of learning styles (4 MAT Model):

a. Imaginative Learners: seek meaning, ask ‘Why?’ they share ideas, and are interested in people and culture

b. Analytic Learners: are interested in ‘What?’ and seek information and facts

c. Common Sense Learners: want to know ‘How does it work?’ and enjoy problem-solving

d. Dynamic Learners: ask the question ‘What if?’ they learn by trial and error and believe in self-discovery

An underlying message from visitor research is that that we can never treat visitors as a homogenous group.

In truth, we – as exhibition developers and storytellers – need to be a lot more humble and not assume we know what works for everyone.

Why do they visit?

Across formal surveys of thousands of museum visitors, it appears that the most common reasons people visit museums are:

1. To be together with people

2. To go somewhere that will be comfortable

3. To enjoy the challenge of a new experience

4. To find an opportunity to learn

5. To do something active (i.e. not staying home to watch television or play video games!)

What are they looking for?

We can never anticipate the multiplicity of reasons for a museum visit. However, we can assume there are some things that all visitors tend to look for when visiting a museum, art gallery, historic place or cultural centre:

Enjoyment – being somewhere special, sometimes sharing it with others

Competence – feeling able to understand what’s going on

Stimulation – being provoked by new thoughts and understanding

Satisfaction – experiencing new things, having questions answered

See Resources and References at the end of this tool to discover more about museum visitors and their needs.

How are visitors affected?

Given the range of abilities and personalities, one must also consider the different contexts that affect our visitors by using a method called

the Interactive Experience Model (3). Through their review of visitor research, John Falk and Lynne Dierking suggest that a museum visit is an interaction among three contexts:

Personal Context

This is different for each person. This is what they bring of themselves when they enter an exhibition: their interests, motivations, concerns, mood

Social Context

This is affected by who the visitor is with. Are they alone or in a group? What type of group – a family, a bus tour, a school group?

Physical Context

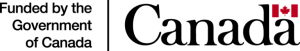

People are affected by the environment they enter: the way it looks, its shape and smell, its textures, the architecture, the ambience.

Photo credit: Tim Willis

While each visitor is unique, visitors do also share some common characteristics. We all respond to stories. And every visitor – well, most of them anyway – is curious about the world.

How do visitors behave?

Research reveals how narrow our window is for an exhibition to have any impact. On average a visit consists of four parts:

- Orientation (3 to 10 minutes).

- Intensive looking (15 to 40 minutes). In this time visitors follow the order intended by the museum.

- Cruising (20 to 40 minutes). Visitors are hoping to see everything but only selecting a few parts.

- Leave-taking (3 to 10 minutes). Visitors are thinking about the exit, the washrooms, where they parked the car, where to eat lunch, and so on.

The timing will certainly depend on the size of your exhibition and museum, but regardless, we have limited time to captivate our visitors.

About museum fatigue

Museum fatigue happens in less than one hour. It is the result of physical and mental overload. In fact, museum fatigue was first studied in 1928. The study established that mental fatigue was more consequential than physical fatigue.

The quality of our storytelling can help mitigate museum fatigue.

Knowing your visitors

It is really important to decide who your exhibition is for. Many museums will respond to this challenge by saying “it’s for everyone.” Of course, a museum aspires to be enjoyed by all. However, it is important to get more specific about your audience when developing an exhibition. Successful exhibitions are particular. They are shaped around what will work for the exhibition’s primary audience. When planning your exhibition’s story, ask yourself a series of questions:

For this exhibition…

- Who do we most want to appeal to? Try to be specific. Who are your main audiences… families, academics, Uruguayan tourists, extra-terrestrials? You should be able to pick a few main categories.

- What sort of age range must the exhibition work for?

- What kind of groups will visit? Schools, tourists, families, seniors?

- What might they already know about this subject?

- In which language(s) do they like being addressed?

- What kind of language excludes them?

If you sketch the answers to these questions onto a large sheet of paper you end up with a profile of your target visitors. That is who you plan, design and write your exhibition for. And if you do the job well, almost all of your other visitors will enjoy it too.

Organizing the Story

Now that we have our visitors’ needs, wants and learning styles top of-mind and once we know who our story is meant to be for…..we can think about the story we want to create.

A great book has parts: an introduction, chapters, a conclusion. Great stories have parts too. They are a little like music: a prologue, moments of tension, moments of rest, a climax and an ending.

The building blocks of a story for a great exhibition are:

- The Big Idea

- Main Themes

- Messages

It is important to organize our exhibit’s story before we begin to design. The first critical idea that should be addressed is: what is the story about?

Finding the Big Idea

Good exhibitions are built around a central idea. It’s like having an “angle”or thesis or point of view. By identifying The Big Idea you are telling the visitor that there is a reason for the exhibition. Good exhibitions have a purpose; without one, the exhibition is simply conveying information.

What is The Big Idea?

- It is only one sentence long.

- It is the central purpose of the exhibition.

- It is the single notion that you want your target audience or visitors to leave with.

- All themes and messages in your exhibition should support The Big Idea.

Visitors will learn about molecular structure, chemical reactions and the scientific process of analyzing unknown substances.

(This example includes several ideas; too many, in fact, and likely none of which the average visitor will understand.)

The settlement of Canada.

(This is a topic; it has no perspective; it is not a complete sentence.)

Sharks are not what you think.

(This idea is simple, challenging; you can hang a whole exhibition around this idea.)

A healthy swamp provides many surprising benefits to humans.

(This idea allows you to explore the nature of swamps and why they are important.)

How do I come up with The Big Idea?

It is not easy to capture the Big Idea; and the challenge is not about wordsmithing. The challenge is making sure your exhibition has a real purpose.

By the way, once you have your Big Idea, it will become the foundation of the introduction to your exhibit.

Find the big idea…

- In a nutshell, what is the exhibition about?

- So what? Why should visitors care?

- What is the most important thing you want visitors to leave with?

Ask yourself three questions. Better yet, do it in a group and write your answers on flip chart paper:

The Big Idea is announced in the introduction to the Smithsonian’s Kenneth E. Behring Family Hall of Mammals: “Welcome to the Mammal Family Reunion! Come meet your relatives.” Photo credit: Reich and Petch Architects.

Now…see if a Big Idea sentence emerges. Remember, this exercise may not be easy, but it is a critical part of the process. Your efforts will be worth it.

Other Building Blocks of the Exhibition Story

Before you start to design, you should figure out all of the main building blocks of your story:

- The Big Idea

- Main Themes

- Messages (the hard information you want each exhibition theme to convey)

The themes and messages should all support and link back to The Big Idea.

Interpretive Plans

What are some parts to consider in an Interpretive Plan?

- The Big Idea

- Visitor Experience Goals

- Learning Objectives

- Interpretive content:

- Themes

- Messages

- Stories

- Assets: objects, specimens, photographs, documents, media

(film, video, audio) - Tools

- Other notes on the Visitors’ Experience

Let’s define some terms:

An Interpretive Plan: a tool for organizing the story. It sets direction or the story, keeps the story organized and captures all the relevant information you’ll need upon which to base your exhibition design.

Big Idea: the central purpose of the exhibition.

Visitor Experience Goal: the effect you want to have on visitors.

Example: Immerse visitors in the sounds and sights of a Viking ship.

Learning Objective: what you want the visitor to take away.

Example: Norse people had a rich and complex culture.

Learning Objectives hold the exhibition accountable. When doing visitor surveys, you can ask visitors what they learned and find out if your Learning Objectives were met.

Theme: a critical idea. Exhibitions might have several themes; all of them should support and link to the Big Idea.

Example: To be Viking meant taking on a mission.

The theme itself may be supported by a series of mini-ideas or subthemes.

Message: hard information that we want to convey to support a theme.

Example: The word Viking means “a man on an adventure.”

Messages can be ranked:

1. Primary Message (what the exhibition must communicate)

2. Secondary Message (what the exhibition should communicate)

3. Tertiary Message (a nice message to include if there is room)

Story: a story that you tell to support your Big Idea, illustrate your theme and convey your messages.

Example: Erik the Red and his journey to Greenland.

Assets: collection objects, specimens, photographs, documents, and/

or ephemera

Tools: labels and text, display cases, graphics, digital media, interactives, live interpreters

As your exhibition project develops, it may be useful to create an Interpretive Plan. Each museum does this differently, but essentially the Interpretive Plan is a way to organize your exhibition’s story and to keep it organized.

Principles of Interpretation

Telling a story clearly and powerfully in an exhibition takes work. It is much easier to communicate straight facts or information. It is harder – but much more effective – to tell a story that connects with the visitor.

In his 1957 book, Interpreting Our Heritage, Freeman Tilden described the principles of interpretation. He said, “Information, as such, is not interpretation. Interpretation is revelation based upon information.” These principles get at the heart of storytelling. Let’s explore each one.

Principle 1

Interpretation must relate to something within the visitor.

The visitor’s main interest is in whatever touches his or her personality, experiences, and values.

Every visitor seeks to be engaged and connect to a story. Visitors do not want to be lectured. How can we turn “information” into “interpretation” – in other words, how can we create a compelling story that engages the visitor’s imagination?

Example: Mammoth on the Grasslands

Information: Mammoths existed in this location 10,000 years ago. They were browsers. They traveled the grasslands in herds.

Interpretation: Let’s pause here for a few seconds. A few thousand years ago, mammoths roamed the plains in great herds. Chances are, they browsed right where you are standing now.

With effective interpretation, the writer speaks to the reader directly and appeals to their imagination.

Principle 2

Interpretation is revelation based upon information.

Great interpretation does not just present the facts or details, it reveals something more.

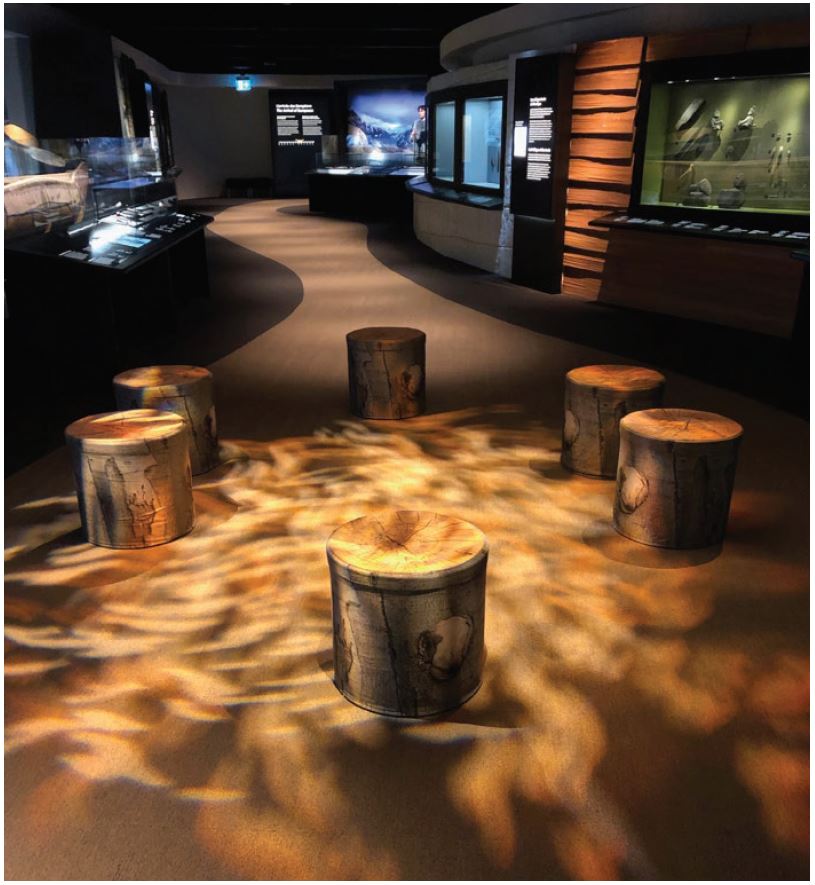

Example: The case of Thelma Barlow’s pass.

Information: In 1941 a German bomber attacked an aircraft factory in England. This worker’s pass was found in the wreckage.

Interpretation: War changed everything. Thousands of women left their homes and families to work in factories to support the war effort. But it was not safe. After a bomber destroyed the factory where she worked, Thelma Barlow’s pass was her only possession that was not destroyed. Luckily, Thelma survived.

Here, the interpretive text reads like a story. More importantly, it moves beyond the fact of Thelma’s pass and the bombing. It reveals that women were working in non-traditional roles. The world had indeed changed.

Objects generally do not speak for themselves, though every object has a story. Our obligation is to find – and then reveal – its story.

Principle 3

Interpretation is an art, which combines many arts.

Freeman Tilden said:

“You can have a sense of joy at hearing a lovely chord without being a virtuoso.”

A successful exhibition is like a piece of orchestral music. It requires many “instruments” to create the beautiful chord.

Example: David Bowie is at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

How many arts are at play here to tell the remarkable story of David Bowie’s influence?

Answer?

At least eight!

1. The Story (or Text)

2. Graphic Design3. Object display

4. Display lighting

5. Lighting effects

6. Video projection

7. Sound

8. Architecture

Although the use of multiple arts within an exhibition is dependent on your museum’s human and other resources, challenge yourself to be creative. Try to incorporate a few extra artistic elements within your next exhibit.

Principle 4

Interpretation is not instruction, but provocation.

Provocation does not necessarily mean to anger or upset people. It can simply be about getting the visitor to think.

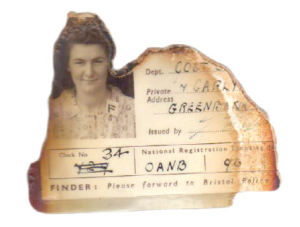

A master class in interpretation is found in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s exhibition: Remember the Children: Daniel’s Story.

This remarkable exhibition invites the visitor to explore Daniel’s home, to discover his letters and journals. It is provocative. We are not meant to emerge from the exhibition unchanged. The objective is to get us thinking. The exhibit and story places us in Daniel’s home – in fact, in his shoes – and challenges us to think:

- How did the Holocaust effect a young child?

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s exhibition: Remember the Children: Daniel’s Story. - What was it like to be under such threat?

- How would I have acted?

The exhibition was a bold move by the Museum, especially when you consider this is an exhibition designed for children; but the museum tells its story well and its interpretation is effective. Few visitors will forget this exhibit or Daniel’s story.

From Remember the Children: Daniel’s Story

Dear Diary,

I feel cut off from the world. There are no

telephones here. There are even rules about

mail. I can only send letters to friends back

home on certain days.

Do they even get my letters?

Daniel

Principle 5

Interpretation must address the whole.

A listing of facts is the best way to bore the visitor. It is far better to be given a glimpse of a bigger picture.

Information: In 1903, women who were part of the suffragette movement in Britain illegally stamped the message “Votes for Women” on pennies.

Interpretation: Power is not given willingly – but taken. On the front side of this coin is a portrait of Edward VII, balding, and powerful… right over his face is the word “Votes,” over his ear, “for” and across his neck, “Women.” The message on the coin was meant to circulate widely and indefinitely.

The British Museum chose this modest object to be part of their History of the World in 100 Objects project. In doing so they give us a marvelous piece of interpretation showing how a simple object has power to be a portal into a bigger world.

Interpretation is the business of breaking the silence that surrounds objects.

Principle 6

Interpretation to children is not a diluted form of interpretation to adults.

Interpretation for children demands a fundamentally different approach.

Children learn by listening, doing, touching,and examining things.

Suburbia is an exploratory 1960s kitchen environment. Content is delivered and discovered along the way.

Principle 7

Be brief.

Remember what was mentioned about “museum fatigue?” Don’t forget that your visitors are usually standing as they explore.

Freeman Tilden urged us to be brief and to cultivate the power of understatement. After all, a beautiful scene is not made more beautiful by calling it beautiful. Freeman was impressed by the way people had, in the past, marked historic sites. Often, he felt that their brevity could teach us a thing or two.

Our long descriptions of events, pale by comparison to a simple great quote.

Example: Historic marker at Lexington Green

Line of the Minute Men

April 19, 1775

‘Stand your ground

Don’t fire unless fired upon

But if they mean to have a war

Let it begin here’

– Captain Parker

The quote from Captain Parker says it all. It was at this site that the opening shots were fired, starting the American Revolutionary War.

Principle 8

It’s about love.

Freeman Tilden captured this notion, years before The Beatles!

He said:

Whatever is written without enthusiasm will be read

without interest. You must be in love with your material

and in turn with your fellow man.

We should be eager to tell our story and share it with our visitors. After all, we are the story’s keeper and our mission is to share it.

When we communicate our story, we must have empathy for – and interest in – the visitor’s situation: their knowledge, their interest and their energy.

We (the Museum) are the host. We should be gracious and kind. While we may have important knowledge to share, we are not above our visitors.

We must always remember our visitors come first.

Final Thoughts

It is hard work to tell stories well. It is much easier to simply relate facts and information. But, seeking the story is worthwhile. It is worthy of our time and energy!

If we tell our stories well, our visitors are more likely to become interested and engaged. And that’s the whole point!

So remember these few parting thoughts:

Know your visitors

Decide which audience(s) you exhibition is for. Rank them. Develop the exhibition for them.

Respect your visitors

Interpretation is about making sure your visitors don’t feel dumb – or numb – in response to what you are saying.

Find The Big Idea

It will elevate the “conversation” between exhibition and visitor if you have a central point. Every good story has a big idea. In fact, every object label has one too.

Use Freeman Tilden’s principles of interpretation

Turn the information into a story. Be provocative. Get creative and be enthusiastic about the story you want to convey.

Be brief

Visitors have limited ability to focus. They become overloaded quickly. Keep it short. Get to the point.

Cultivate self-criticism

Learn through observation what works and what does not. Don’t be afraid to start again.

Further Reading and Resources

About Visitors

About The Big Idea

Exhibit Labels: An Interpretive Approach. Beverly Serrell. Walnut Creek, Calif: AltaMira Press, 1996; read Chapter 1, Behind it All: A Big Idea

About Storytelling

Interpreting Our Heritage. Freeman Tilden. University of North Carolina Press, 2007

About the Art of Writing for Exhibitions

Check out the BCMA Brain for more resources on Exhibition Development, including Interpretation Principles 2: The Art of Writing for Exhibitions.

Login to BCMA’s member portal to access an archived webinar with Tim Willis entitled Planning Successful Exhibitions: Learning from failure, planning for success (BCMA webinar, February 2018)

Once you have developed the art of storytelling....consider applying to the Virtual Museums of Canada Community Stories Investment

program. The program supports the development of virtual exhibits for small, community based museums.