An introduction to Blockchain, Cryptocurrency, and NFTs

Climate Catastrophe, Cons, and Colonialism

The world of the blockchain (a technology that is currently being rebranded as “Web3”) is complex, obtuse, and often seems to defy conventional logic. If you feel mystified by technologies like Bitcoin or NFTs that’s perfectly normal – the blockchain is obtuse by design.

2023 Update: Since this article was published in 2022 a lot has changed in the world of the blockchain. This 2023 update corrects some information which is now out of date and brings some additional context from the past year.

Quick Links:

This article is long and covers a number of technical and confusing topics, so if you want the gist, know that the original title of this piece was “Why Everything Related to the Blockchain is Bad and Anyone Who Tells You Otherwise is Lying or Mistaken.” While this article will attempt to provide a basic understanding of what this technology can do, what it can’t do, and why you should be extremely skeptical about its adoption into more elements of our society, if you take anything away from reading this, remember, blockchain technologies magnify the very worst parts of our exploitative, capitalist society and any potential future good these technologies offer pale in comparison to their present and future harms.

This article is long and covers a number of technical and confusing topics, so if you want the gist, know that the original title of this piece was “Why Everything Related to the Blockchain is Bad and Anyone Who Tells You Otherwise is Lying or Mistaken.” While this article will attempt to provide a basic understanding of what this technology can do, what it can’t do, and why you should be extremely skeptical about its adoption into more elements of our society, if you take anything away from reading this, remember, blockchain technologies magnify the very worst parts of our exploitative, capitalist society and any potential future good these technologies offer pale in comparison to their present and future harms.

Museums and museum professionals are highly trusted by society. Since the field occupies this rare position of trust, it is critical that we engage with new concepts, technologies, and discussions that are happening in the broader society as we can help our communities unpack new ideas and through dialogue make sense of the world. If you’ve been wondering about what things like Bitcoin, DAOs, or Blockchains are, this article will give you a basic historical, technical, and social of this much-hyped technology.

What is Web3?

While definitions and distinctions between Web 1.0, Web 2.0, and Web3 (“Web3” is more commonly used than “Web 3.0”) vary depending on who you talk to, generally speaking, these terms are used to describe the history of the internet in the following way:

Web 1.0

- Early internet to the late 1990s

- Internet is defined by static web pages with limited interactivity

Web 2.0

- Late 1990s/early 2000s to late 2010

- Internet is defined by user-generated content and interactive social media

Web 3.0

- Present-day to future

- Blockchain technologies create a freer, more open web

When thinking about these terms it is important to remember that Web 2.0 and Web3 are both forms of branding. Web 2.0 was popularized to brand changes in web design and function from earlier trends and functions, to make the companies and websites that were being created and marketed appear new and different.

In a 2006 interview Tim Berners-Lee, a founding figure in the creation of the Internet, had this to say about the term Web 2.0:

“Nobody really knows what it means… If Web 2.0 for you is blogs and wikis, then that is people to people. But that was what the Web was supposed to be all along… Web 2.0, for some people, it means moving some of the thinking [to the] client side, so making it more immediate, but the idea of the Web as interaction between people is really what the Web is. That was what it was designed to be… a collaborative space where people can interact.”

And if “nobody really knows what [Web 2.0] means,” then Web3 takes the empty branding of its predecessor to new heights. Web3 promises a freer and more open web in which tech monopolies no longer act as gatekeepers of information and commerce (reflecting the core libertarian ideological origins of the technology, but more on this later).

The website Ethereum.org (created in 2015, Ethereum is the second-most used cryptocurrency in the world next to Bitcoin) states that under Web 2.0 “payment service may decide to not allow payments for certain types of work,” whereas under Web3 “payment apps require no personal data and can’t prevent payments.”

In this respect, Web3 promises to be freer than Web 2.0 – but what does this look like in practice? Currently, many major financial platforms like Visa, Mastercard, and PayPal have suspended operations in Russia due to the country’s invasion of Ukraine, however, many Russian oligarchs are reportedly using Web3-based Cryptocurrencies to avoid global economic sanctions. In this instance, the freer, more open internet promised by Web3 is not without fault – an unregulated web has as much capacity for harm as it does for good.

Again, just as Web 2.0 was an attempt to brand internet trends, Web3 is an exercise in spin. Ideas like user-created content and social networks that are core to Web 2.0 do not inherently lend themselves to centralized control. A combination of market forces, lack of protection against monopolies, and the centralization of capital behind massive tech corporations made Web 2.0 dominated by internet gatekeepers. If the ideals of Web 2.0 can be centralized, it stands to reason that the freer, more open internet promised by Web3 may be just as vulnerable to monopolies. When assessing the promises made by Web3 proponents, it is important to critically assess their claims for the future against examples from the past and the realities of today.

Further readings:

What is Cryptocurrency?

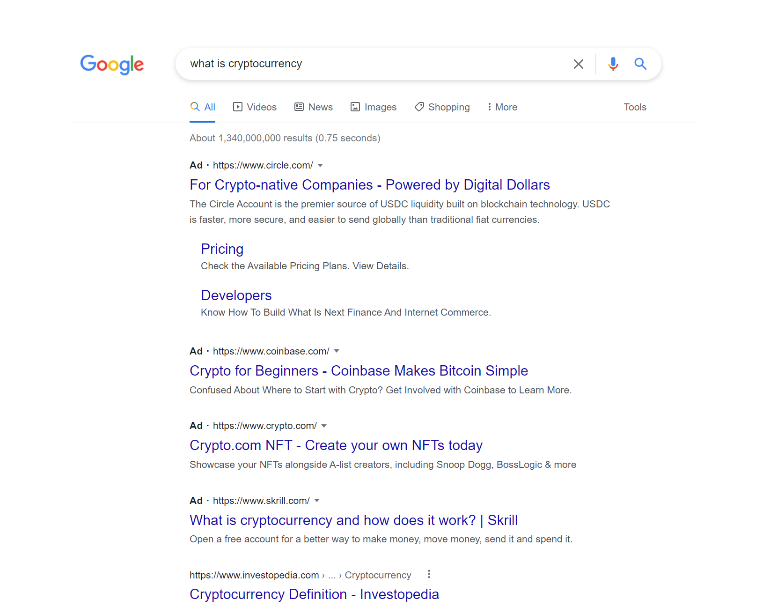

Of all the Web3 applications, cryptocurrency is probably the most widely known, especially in its most popular form, Bitcoin. If you’ve ever wondered what cryptocurrency is, Googling the term isn’t the most helpful way to critically inform yourself because the top results are dominated by sponsored search results and investment sites attempting to sell you cryptocurrency.

Since so many sites have a vested interest in selling different cryptocurrencies and encouraging investment and speculation, finding information that offers a critical perspective can be challenging, especially for people who are just starting to learn about Web3.

Wikipedia offers a reasonable definition of cryptocurrency that I will attempt to unpack:

Wikipedia Definition

“A cryptocurrency, crypto-currency, or crypto is a digital currency designed to work as a medium of exchange through a computer network that is not reliant on any central authority, such as a government or bank, to uphold or maintain it.”

I’ve bolded three core concepts in this definition. Cryptocurrency is a “digital currency,” meaning that it uses a digital medium and does not have a physical counterpart, unlike national currencies which typically have both digital and physical forms (for example, $1 CAD can be represented both as a digital currency in your online bank account or as a physical currency in the form of a loonie). Cryptocurrency is a “medium of exchange,” meaning that it can be traded between individuals for goods, services, or other forms of currency. And cryptocurrency is “not reliant on any central authority,” meaning that unlike, for example, the Canadian dollar that is backed by the nation of Canada, cryptocurrencies are not backed by a central bank, state, or company.

So are cryptocurrencies made up? In short, yes, but so are all forms of money. While cryptocurrencies don’t have any inherent value because they are purely digital, most forms of currency also do not have any inherent value – unless you can eat it or use it for shelter, currency, whether Canadian dollars or gold bars, only have value because we as humans agree to assign them value. If enough people agree that something has value and those people agree to trade it for goods and services, cryptocurrency is just as real or as fake as any other form of currency.

We will go into the history of cryptocurrency later on in this article, but it is important to note that in the 13 years since Bitcoin was created, the value of cryptocurrency currency has grown from basically nothing to more than $1,220,000,000,000 (one trillion dollars) worldwide. Cryptocurrency is an extremely volatile market with the values of individual currencies changing wildly from minute to minute, but on the whole, the cryptocurrency market has continued to grow and shows no signs of going away. It is worth noting that since the publication of this article, the global value of all global cryptocurrencies increased by approximately 2.2%, underperforming against the global inflation rate (8.3%) and most major stock exchanges (for example, the Nasdaq increased by an average of 5.78% during the same period). This means that over the past year, more traditional forms of investment have yielded better returns than the cryptocurrency market.

At the same time, however, the purchase and trade of cryptocurrency is still very niche, with Pew Research estimating that only 16% of Americans say that they have ever purchased or traded cryptocurrency of any sort. And within that subset of people who have used Cryptocurrency, it is estimated that roughly 0.01% of users control more than 27% of all cryptocurrencies in circulation. And this statistic helps to contextualize why so many of the top search results for “what is cryptocurrency” are either ads or investment-friendly sites – the cryptocurrency market isn’t widely popular and is dominated by a heavily-invested few, if this 0.01% can attract more users and more investment, they have more to gain than anyone. Cryptocurrency proponents see the 84% of people who are not invested as an untapped market for growth and for this reason, it is important to assess online information of Web3 and cryptocurrency through a critical lens and ask yourself, “is what I’m reading trying to sell me something?” All too often the answer is yes, and as this article attempts to demonstrate, the product Web3 is selling generally comes with a tremendous cost.

Why Do Cryptocurrencies Burn Carbon?

Another important thing to know about cryptocurrencies (and Web3 in general) is that it adds unimaginable amounts of carbon into the atmosphere and burns tremendous amounts of energy. As this 2021 New York Times articles states, “The process of creating Bitcoin to spend or trade consumes around 91 terawatt-hours of electricity annually, more than is used by Finland, a nation of about 5.5 million.” For a more local example, in 2018, British Columbia generated 74.2 terawatt-hours (TW.h) of electricity. Bitcoin consumes more electricity each year than the entire province of BC generates between its wind, solar, hydroelectric, and natural gas energy production.

But why do cryptocurrencies use so much power? Cryptocurrencies, like Bitcoin, are generally “mined” from a “blockchain” and the mining process involves using specialized, power-intensive computers to complete increasingly complex mathematical equations that use ever-increasing amounts of power to compute. Because cryptocurrency mining is so energy-intensive, many mining operations will move around the world to seek out countries and regions with the cheapest access to electricity. Until 2021 China was home to roughly 70% of all Bitcoin mining in the world until the country’s government instituted a mining ban, in part, to curb the amount of energy being consumed by the industry.

While the details of why cryptocurrency mining requires the use of so much power and the ecological impact of Web3 technologies will be explored in detail later on in this article, I cannot stress enough that currently, cryptocurrencies are an ecological disaster. At a time when the impact of human-accelerated climate change is becoming more deadly and the need to decarbonize our society is more apparent, cryptocurrencies are throwing fuel onto a fire that will consume us all, all for the sake of making a tiny sliver of our population wealthier. There are no number of Telsas crypto-proponents can purchase, no number of carbon offset credits they can invest in, no number of “green start-ups” that can get off the ground that can possibly undo the harm that the needless burning of hundreds of tons of carbon is causing for our planet’s future.

Since the initial publication of this article in 2022, there has been a significant development in the carbon output of the popular cryptocurrency Ethereum. In September 2022 Ethereum completed The Merge (they choose to capitalize the “t” in “the”). The Merge has shifted how Ethereum is mined from a “proof of work” model (i.e. a model that uses massive amounts of electricity to solve increasingly complex mathematical problems) to a “proof of stake” model (one in which a network of “validators” are used to verify the authenticity of block on the blockchain). This shift has reduced the amount of carbon consumed by Ethereum by approximately 99.988%. Before this shift, Ethereum consumed about as much annual electricity as the entire country of Bangladesh. While this shift will greatly reduce the future carbon footprint of Ethereum, the currency still has a massive carbon debt from its past emissions.

It is good that many (though definitely not all) are shifting to less carbon-intensive forms of verification, but it does not change the reality that the global cryptocurrency sector has generated unfathomable amounts of carbon and e-waste purely to further unfettered capitalism. Even if the future is more sustainable, one must ask the question – was the carbon and waste created to date worth it?

Further readings:

What Is the Blockchain?

Cryptocurrencies, NFTs, and DAOs are all based around the core concept of “the blockchain.” Using a cryptocurrency (like Bitcoin) as an example, each Bitcoin transaction is grouped into blocks with each block having a cryptographic hash (a unique, fixed number that is used to identify and verify the transactions, similar to a book’s ISBN number or the bar code on a product). This unique number, or block, is part of a broader interlinked chain with each block on the chain helping to verify the authenticity of the other blocks on the chain. Because all of the blocks on the chain help to verify the others, forging a block is nearly (though not entirely) impossible.

Another way to view a blockchain is to think of it as a “distributed ledger,” meaning that each time a transaction is made, the network distributes copies of this transaction to all the blocks on the chain, ensuring that any one block has a record of the whole chain.

What is an NFT?

Update: Since the publication of this article, the NFT market seen a global downturn, with spectacular examples like an NFT of the first Tweet ever written that sold at auction in 2021 for $2.9 million, up for auction for around $2,000 in 2023.

NFTs, or non-fungible tokens (i.e. an item that is unique and cannot be replaced with another identical item), are digital assets that can be owned, sold, or traded but cannot be altered or copied. The blockchain is used to “mint” (i.e. confirm the authenticity of) an NFT, with many NFTs using the Ethereum blockchain.

The digital asset being sold or traded is not the NFT itself.

If the BCMA were to sell this digital asset as an NFT, we would mint an NFT on the Ethereum blockchain, creating what is essentially a digital contract. What this digital contract verifies depends on the specific agreement. Some NFTs give the owner full ownership and control of the copyright and use of the image. If this were the case, the buyer of the owl NFT would be allowed to reproduce it or license the use of the image to third parties. However, in some NFT agreements, the artist retains the copyright over the image itself. In this situation, the buyer of the NFT owns this specific instance of the image, but not reproductions of it (you could almost think of this as if the owner controls “Money_Owl_001.jpeg” but not “Money_Owl_002.jpeg”).

One of the more confusing aspects of NFT is that only the token (i.e. the blockchain record) is non-fungible, the digital asset associated with the token remains fungible. In other words, even if someone owns the NFT of the owl, there is nothing stopping anyone on the internet from taking a screenshot of it or right-clicking to download the jpeg. In some ways, it might be helpful to think of NFTs like numbered prints – each print is identical, but its unique number gives the print greater value.

As of the writing of this article, the creation, sale, and trade of NFTs are responsible for millions of tons of carbon being added to the Earth’s atmosphere, hastening global climate change and threatening all life on the planet. While this may sound dramatic, it is important to remember that no matter the value or utility of NFTs, at this point in history, their existence further increases the likelihood of catastrophic climate change and any potential good must be weighed against their current harm.

Since the use of NFTs is relatively new, there are not yet peer-reviewed studies that quantify the environmental impact of a single NFT. The website cryptoart.wtf estimated the carbon footprint of “Space Cat,” an NFT GIF of a cat in a rocket, was similar to the amount of carbon used by a resident in the European Union over a two-month period. While there is a degree of debate over whether all NFTs on the Ethereum blockchain create that degree of carbon, it is safe to assume that NFTs as a whole create a tremendous amount of unnecessary greenhouse gas emissions.

But many Web3 proponents promise that a greener future is on the horizon. As already mentioned, most common cryptocurrencies use a “proof of work” to secure the legitimacy of their blockchains. Proof of work requires increasingly complex computing that uses massive amounts of electricity.

However, blockchains can also be secured through a process called “proof of stake.” Before trying to define what proof of stake means, please note that like many Web3 terms and ideas, this involves a lot of jargon and is incredibly byzantine – if this doesn’t make sense to you, the problem lies with the technology, not with you. PCMag defines “proof of stake” thusly:

“Delegated PoS is a variation of PoS that is considered to be more democratic. Rather than being the miner that adds the block based on the total amount of crypto at stake, crypto holders use their stake to vote for other miners, which are known as “witnesses,” “super representatives” or “validators.” The delegates do the mining and are rewarded with newly created crypto plus transaction fees until they are voted out and new delegates are voted in.”

– PCMag

Basically because proof of stake relies on community verification and not mathematical verification far less computing power is needed and therefore its carbon footprint promises to be dramatically smaller. A recent article in Recode compares proof of stake to a raffle in which people with blocks on a specific cryptocurrency’s blockchain are randomly selected by an algorithm to receive more of the currency, and much like a raffle, those with more “tickets” have a higher chance of winning. So while proof of stake uses less energy and computing power, it is no more democratic than proof of work, because it inherently gives the wealthy (i.e. those with more of a specific cryptocurrency) a greater chance of becoming wealthier by being algorithmically chosen to receive more cryptocurrency.

Further readings:

A Brief History of Cryptocurrency and the Blockchain

While Bitcoin, the best-known cryptocurrency was created in 2008 by an unknown person (or possible group of people) using the name Satoshi Nakamoto, the idea of a trustless form of digital currency goes back to the early days of the internet itself. The history of cryptocurrencies is intrinsically linked to libertarian ideology.

In 1983 the American cryptographer David Chaum created “digital cash,” a digital currency that used cryptography to secure and verify transactions. In 1989 Chaum founded DigiCash Inc in an attempt to popularize his new digital currency. Chaum marketed DigiCash as a way to bank and transfer money online in a way that was untraceable to banks, governments, or any other parties. In 1989 DigiCash declared bankruptcy and the company was sold for its assets.

In 2009 Satoshi Nakamoto launched the Bitcoin protocol and the first Bitcoin transaction took place on the 12th of January. The first purchase made using Bitcoin occurred in February 2010 when someone paid 10,000 Bitcoin for two pizzas (at the time of writing this, 10,000 Bitcoin would be worth nearly half a billion Canadian dollars).

But to understand why protocols like DigiCash and Bitcoin were created, one must understand the interconnection between cryptocurrency and libertarian ideology. Broadly speaking libertarians strive towards maximizing their individual autonomy while minimizing the role of the state in their lives. For many extreme libertarians, the concept of money is problematic because most currencies drive their perceived value and stability from governments. In other words, a Canadian dollar has value because it is guaranteed by the Government of Canada. And if all major currencies derive their value from nation-states, anyone who uses these currencies to store their wealth must accept to some degree the authority of the state.

With the rise of computers and the internet in the 1980s and 90s, libertarian-leaning thinkers began to imagine how technology could create a state-less form of currency. In the 1997 book “The Sovereign Individual,” authors James Dale Davidson and William Rees-Mogg envisioned a future “cybermoney” that could be used to undermine the nation-state, writing:

“This new form of money will reset the odds, reducing the capacity of the world’s nation-states to determine who becomes a Sovereign Individual. A crucial part of this change will come about because of the effect of information technology in liberating the holders of wealth from expropriation through inflation.”

Satoshi’s decision to fix the supply of Bitcoin to 21 million coins was a conscious decision to help create a fixed currency immune to inflation – a perennial fear of libertarians. In this respect, the technological underpinnings of Bitcoin reflect the ideological underpinnings of its creators.

Now, let’s be clear, the current global status quo of state-sanctioned capitalism causes untold amounts of harm, both in terms of human suffering and in terms of environmental exploitation. There is merit in imagining new ideas for sharing and storing wealth that rejects the status quo and attempts to build a more equitable and sustainable world, but cryptocurrency is not this. Cryptocurrency attempts to preserve the autonomy of the individual over all else, not the greater good of society. For this reason, it should be of little surprise that many proponents of cryptocurrency prioritize their own wealth and status in relation to the technology and adoption over its serious ecological and humanitarian impact

Further Reading:

Blockchain, Web3, and Colonial Exploitation

While much of this article has focused on the impact of Web3 in terms of energy usage or carbon created, the damage inflicted by these technologies also reinforces colonial exploitation in ways that further perpetuate violence against people in the Global South and historically exploited communities. The colonial harms of blockchain technologies, and the largely white, wealthy, men who proselytize them, can take many forms, but repeat far too common patterns of exploitation.

Ecological Impact Beyond Carbon

Cryptocurrency mining creates tremendous amounts of e-waste. “Mining rigs,” specialized computer systems that are so specifically designed for cryptocurrency mining that they cannot really be used for other purposes, typically have a lifespan of between 18-24 months. It is now estimated that the e-waste generated annually from discarded mining equipment is roughly equivalent to what the entire country of Luxembourg throws out in trash each year (about 25 million pounds).

Cryptocurrency mining is driving massive demands for computer graphics cards (an essential tool for processing the complex math required to mine cryptocurrency). This means that new graphics cards are constantly being built, using either recycled materials from old cards or new materials made from rare-earth minerals – both of which have a tremendous human and environmental impact.

As this blog on e-waste explains,

“E-waste contains a laundry list of chemicals that are harmful to people and the environment, like: mercury, lead, beryllium, brominated flame retardants, and cadmium, i.e. stuff that sounds as bad as it is. When electronics are mishandled during disposal, these chemicals end up in our soil, water, and air.”

The single biggest impact that society can have on the production of e-waste is to produce less e-waste. While recycling methods are becoming more and more sophisticated and there are many charities and programs that seek to reuse unwanted materials, “reduce” is the single most impactful point of the three r’s. And yet, cryptocurrency mining has increased the demand for electronics and the production of e-waste to new heights.

According to a United Nations report entitled “Waste Crimes,” a substantial portion of global e-waste is exported to West Africa and Asia where this waste is frequently processed in dangerous conditions, harming both local peoples and the environment. This makes cryptocurrency an extractive process that enriches an elite few while creating hazardous materials that are then shipped to the Global South – the rich reap the reward of cryptocurrency while the poor are left with the consequences.

“Crypto colonizers” in Puerto Rico

In 2017 Hurricane Maria devastated the northeastern Caribbean, inflicting tremendous damage and suffering in Dominica, Saint Croix, and Puerto Rico. Shortly after the hurricane passed, a number of cryptocurrency millionaires and billionaires promised to donate money, bring investment, and ultimately build a “crypto paradise” in Puerto Rico. Backed by government support in the form of tax breaks and laws that allow newcomers from tax-free investments, the island saw a surge of cryptocurrency enthusiasts move to Puerto Rico, driving up house prices, gentrifying local communities, and leading to these newcomers being referred to as the “crypto colonizers.”

In the wake of a deadly storm that killed 3,000 people and left Puerto Rico’s 3.4 million residents without power, running water, or cellphone service for weeks, this influx of crypto-enthusiasts brought with them the promise of rebuilding and reinventing Puerto Rico into a crypto utopia. But as a story in the Washington Post notes:

“But they offered few concrete details. At the time, blockchain had few viable uses beyond virtual currency, which early adopters, many of whom were libertarians, saw as a tool to circumvent taxes and other forms of government oversight. The 2017 boom was driven by a flood of initial coin offerings, or ICOs, in which investors pumped money into often speculative projects in exchange for tokens. In Puerto Rico, some people quickly sized up the crypto settlers, fat on get-rich-quick schemes, as exploiting the beleaguered island to write their own rules.”

Further Readings:

DAOs and Blockchain Governance

DAOs, or Decentralized Autonomous Organizations, have grown to relatively recent prominence as a Blockchain-powered, non-hierarchical form of community governance and decision making. Recently a group called ConstitutionDAO made headlines by raising $47 million in cryptocurrency in a failed attempt to purchase an original copy of the US constitution.

ConstitutionDAO raised around $47 million in the cryptocurrency Ethereum in a manner akin to crowdfunding. In exchange for each 1ETH (i..e one Ethereum token) donated to ConstitutionDAO, the donor would be able to redeem one million “governance tokens,” which were called $PEOPLE. ConstitutionDAO would then allow $PEOPLE holders to use their governance tokens to vote on all decisions made by the DAO. If ConstitutionDAO had been successful in purchasing the copy of the US constitution, $PEOPLE holders would have voted to decide what to do with it. For a full breakdown of the rise and fall of ConstitutionDAO, I recommend this article from Vice News.

It is estimated that the Ethereum network annually used 99.6 Terawatt-hours of electricity—more power than is required by the Philippines (a country of 110 million) or Belgium (a country of 11.5 million). A single Ethereum block required 220 kilowatt-hours of electricity to mine, which is the same amount of power that an average U.S. household consumes in 7.44 days.

Blockchain proponents claim that DAOs have the potential to transform collective decision-making and even not-for-profit governance through a more “pure” form of democracy. But let’s be honest, groups like ConstitutionDAO are not democracies, they are oligarchies in which decisions are based on wealth. ConstitutionDAO did not give each person one vote, they linked the number of votes each individual had to the amount of capital they could invest.

Recently BuildFinance DAO was dissolved as part of a “hostile takeover” in which one individual managed to obtain enough voting tokens to drain the DAO’s treasury of nearly $470,000 in cryptocurrency. According to BuildFinance, “As things stand, the attacker has full control of the governance contract, minting keys and treasury. The DAO no longer has control over any part of the key infrastructure.” However, many have rightly pointed out that this instance can’t really be considered a “hostile takeover” because as a majority vote-holder the “attacker” was well within their rights to “democratically” make decisions about the DAO. Since one person can acquire multiple votes, then a majority vote-holder can act with impunity.

Despite claims of “innovation,” DAOs offer little that is new when it comes to governance and community decision-making (unless you count finding an innovative way to make online polls use exponentially larger amounts of electricity than, say, a Doodle Poll).

Why This Matters to Museums

The Blockchain is coming for museums, whether we like it or not. This is a technology that is dramatically worsening global climate change, is founded in toxic Libertarian ideals, reinforces systems of colonial violence, and allows countries like North Korea (a country that is literally keeping unknown thousands of its citizens in death camps) to avoid global economic sanctions. I urge you as the reader of this article to ask yourself if the potential benefits of Web3 outweigh the harms caused by its increasing ubiquity in our society. For me, the answer is an unequivocal “no.”

Museums, galleries, and cultural institutions are increasingly being used to help legitimize Web3 technologies and it is critical that we as cultural professionals have enough of an understanding of these byzantine technologies to make informed decisions.

Thus far museums, galleries, and cultural institutions have experimented most with NFTs, with most creating digital replicas of items in their collections. In 2021 Uffizi Gallery sold a Michelangelo NFT for $170,000*. Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia minted copies of their Monets, van Goghs, and da Vincis to sell as an NFT fundraiser in 2021. Most museums and galleries experimenting with NFTs have basically used them like limited edition re-prints, creating finite digital copies of famous works for resale.

*Update: Since 2021 more information about this NFT has come to light. The Uffizi Gallery made a deal with Milan-based company Cinello to produce NFTs of works in their collection. While the NFT sold for $170,000, the gallery agreed to split sale costs 50/50 with Cinello and pay a “product cost” surcharge. This means that when the gallery sold an NFT of Doni Tondo in 2021 for 240,000 Euro, the gallery made 70,000 Euro, and Cinello made 170,000 Euro.

In his article, Museums and the NFT Hype, Sandro Debono notes that the adoption of NFTs by museums and galleries runs contrary to the cultural sector’s broad belief in open access policies. For decades more and more cultural institutions have embraced the idea that digital images in their collections should be made available free of charge since cultural institutions hold their collections in the public trust. NFTs introduce the idea of ownership and digital scarcity to digital images, reversing progress towards providing the public greater access to online collections.

This also raises the question of who owns a museum’s collections. If collections are held in the public’s trust, do museums have the moral authority to mint NFTs and sell exclusive rights to replicas of these collections? I would argue that the NFT trend also reverses decades of incremental progress museums have made in supporting the repatriation of their collections. Selling NFTs of their collections calls to mind antiquities trading. What happens if a digital replica of an object is sold to a private collector and then the physical object is later repatriated to the object’s descendant family or community? What if alongside an NFT a museum sells reproduction licenses of a digital replica and the buyer decides to reproduce the replica in a way that the museum objects to?

Even if one ignores the environmental, humanitarian, and ethical critiques of NFTs and Web3, the very nature of the technology is at odds with the progress museums, galleries, and cultural institutions have made toward becoming more open, accessible, and responsive to communities.

Further Reading:

Conclusion

It is entirely possible that this article will not hold up to the test of time. Perhaps Web3 will solve its environmental impact. Perhaps Web3 will find its “killer app” and the utility of the technology will be validated. Perhaps Web3 will become so ingrained in our society and daily lives that we will have little choice but to engage with the technology. But just because proponents of Web3 and the Blockchain say that the mainstream adoption of these technologies is inevitable, doesn’t mean that we must accept this. We have power and agency in building the future we want to see, and museums have more power than we often give ourselves credit for.

Museums are amongst the most trusted institutions in our society and in an age where the very concepts of truth and reality are under attack, trust is powerful. People trust museums, galleries, and cultural institutions to help them make sense of the world. We can bring people together. We can challenge how people think. We can help to unpack extremely complex events and histories.

As museum workers and cultural professionals, it is critical that we don’t shy away from having opinions and using our voices. Museums are not neutral. Museum work is not neutral. If we don’t use our voices to help our communities, louder voices will prevail.

At the beginning of this article I wrote that Web3 and the Blockchain are obtuse by design – they are intentionally confusing because their proponents want you to not engage critically with them and simply accept their inevitability. If you check out from the discussion, it allows people with louder voices to dominate the conversation around them.

I believe that a better world is possible. One that is more sustainable, one that helps people take better care of each other, and one that values life over profit. Through this article, I tried to demonstrate how Web3 and the Blockchain and fundamentally antithetical to this better world. If you also believe that a better world is possible, I urge you to think about how you can use your voice as a museum professional to not be neutral, to have opinions, and to fight for a future worth living in.