Semá:th Xo:tsa Sts’ólemeqwelh Sxó:tsa

By Kris Folds, Curator of Historical Collections, & Adrienne Fast, Curator of Art and Visual Culture, at The Reach Gallery Museum

John Keast Lord was among the men who accompanied the 1859 boundary survey of Stó:lō Téméxw, what we now know as the Fraser Valley. In his 1866 book, The Naturalist in Vancouver Island and British Columbia, Lord recalled his impressions of Sumas Prairie, the lake that filled it, and the surrounding timbered hillsides. He recorded his memories of the freshet-driven spring flooding experienced by the crew and described the following surge in the abundance of flora and fauna as beyond anything he had ever witnessed elsewhere.

This land and its habits may have seemed unprecedented to men like Lord, but it was intimately familiar to the original inhabitants, the Stó:lō People, whose way of life revolved around the Sumas Lake—what they called Semá:th Xo:tsa—and its regular flooding. The lake and its watershed provided a habitat for huge numbers of resident and migratory fish, birds, and mammals. The Stó:lō cared for the resources provided by their Creator through a multitude of sustainable harvest practices and crop management techniques. The Stó:lō systems worked in harmony with the cycles of flooding.

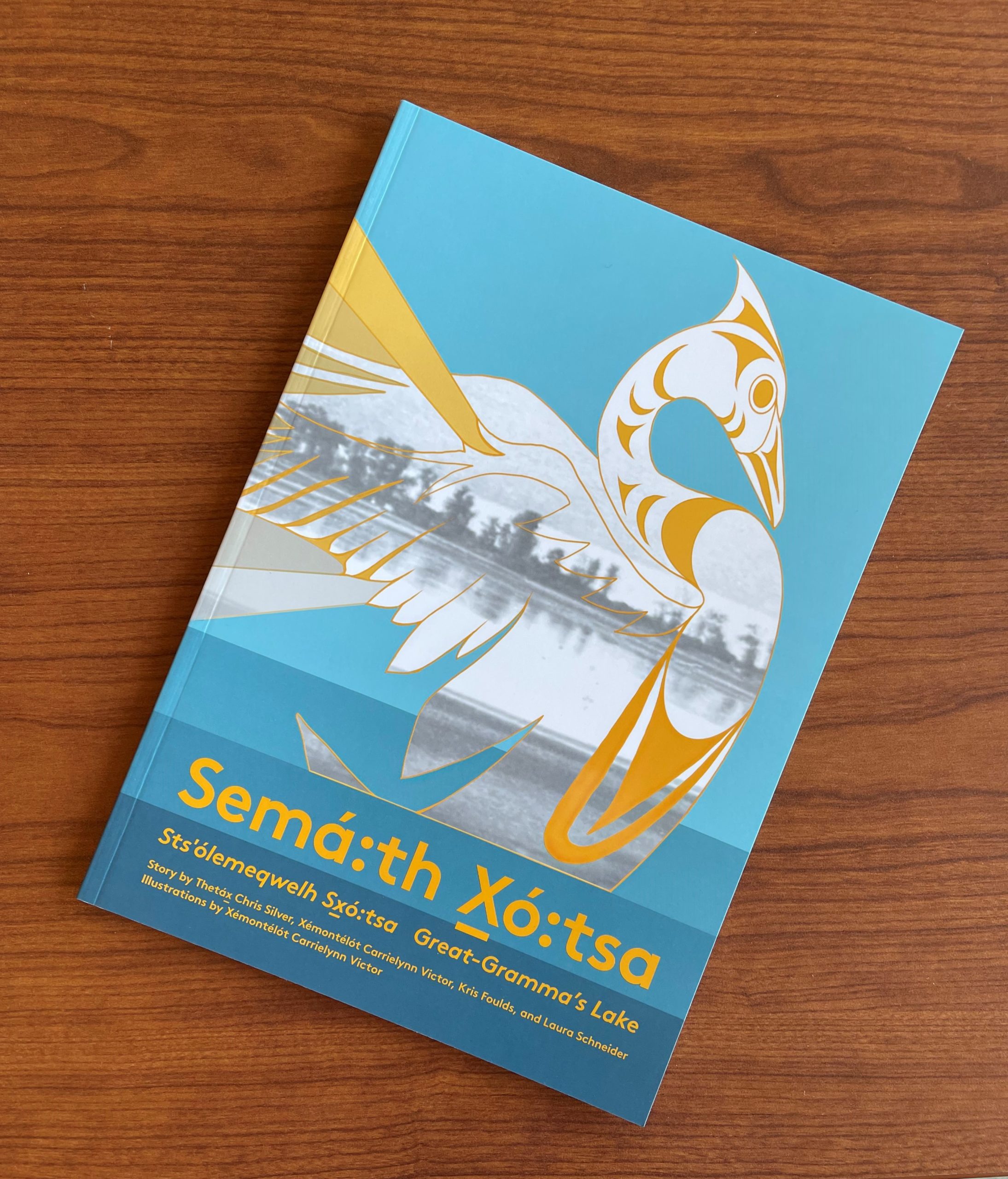

Semá:th Xo:tsa Book Cover. Credit: The Reach Gallery Museum

The same could not be said for the xwelítem, “the hungry ones” (the name given to European settlers by the Stó:lō). Drawn first by gold but interested in profiting from all of the resources Stó:lō Téméxw had to offer, the colonists sought to quantify and settle the land through farming. The very idea of tying themselves permanently to a site placed them at odds with the lake’s natural cycles, enmeshing them in ongoing annual struggles against the forces of nature. The settlers despaired of these struggles and were eventually successful in petitioning the government to intervene. Between 1919 and 1924, a network of canals, dykes, and pump houses was constructed to transform the lakebed into an agricultural resource aimed at benefiting the settler population and promoting increased agricultural revenues. This drainage of Semá:th Xo:tsa had—and continues to have—a profound impact on the lives and livelihood of the Stó:lō People.

Moquem Carrielynn Victor illustration on The Reach archival photo. Credit: The Reach Gallery Museum

Located on Stó:lō Téméxw, in the unceded territories of the Semá:th and Mathxwí First Nations (also part of Stó:lō Nation), The Reach Gallery Museum decided to take a backward glance at this legacy. To reclaim the memory of the lake, the Reach initiated a collaborative, multidisciplinary partnership with a number of Stó:lō leaders and knowledge keepers. Through a series of interrelated projects that include a children’s book, an exhibition, a series of puppet performances, and a storybook walk, we have since sought to work respectfully and cooperatively with our Stó:lō hosts to build intergenerational and intercultural understanding about Indigenous history, land, and resource use in the Fraser Valley.

The hundred-year anniversary of the drainage of the lake seemed an opportune time to meaningfully engage the public in these topics. In 2018, we mounted the first of what has become annual performances using large-scale puppets based on animals that would have lived in and around Semá:th Xo:tsa. In 2019, we formed a small group to co-write a story aimed at young people, in which a Stó:lō elder tells her grandson about the lake and its relationship to their ancestors and community. In 2020, the book was published, and copies were freely distributed to Stó:lō communities and elementary school classrooms throughout the Fraser Valley. We also turned the storybook into a stand-alone exhibition, which opened at The Reach in September 2020 and, due to popular demand, was extended to May 2021. Related educational resources have been enthusiastically taken up by parents and educators, and are used in homes and classrooms across the region.

Digital Planning for the Cultural Sector, Professional Development Certificate

Position your organization to thrive in a digital economy.

This micro-credential looks at ways technology is being used in the cultural sector and gives you the in-demand knowledge and skills you need to help your organization thrive in the digital economy. Embrace the opportunity that technology in the cultural sector can offer. BC residents are eligible for 25% tuition subsidy.

In many ways, the draining of the lake represents a critical moment in the colonial history of the Fraser Valley—one that is emblematic of the ongoing differences between settler and Indigenous perspectives about natural resource management, sovereignty, and Indigenous rights and title. When we began our work, we were keenly aware that these topics remain highly relevant in today’s political context, but we could not have foreseen just how prescient the project would become.

In November 2021, when an atmospheric river delivered record-breaking rainfall that resulted in devastating flooding throughout BC, taking its worst toll in Sumas Prairie, the word commonly used to describe the event was “unprecedented”. Even though the environmental and cultural consequences of the drainage project continue to reverberate into the present, this response showed that the story of the lake is known to surprisingly few Fraser Valley residents of settler descent. But for the Stó:lō, nothing about this history was unprecedented. If anything, these recent events should finally place Indigenous knowledge keepers at the heart of flood mitigation planning.

Luminous Waters 2021 Performance. Credit: Rachel Topham Photography

Through the development of Semá:th Xó:tsa: Sts’ólemeqwelh Sxó:tsa (Great-Gramma’s Lake), co-authors Thetáx Chris Silver, Xémontélót Carrielynn Victor, Kris Foulds, and Laura Schneider sought to reclaim the memory of the lake and reframe the discussion of it in ways that can help audiences understand and participate in the complex subjects of land and resource use in the Fraser Valley. Working closely with Stó:lō collaborators at every step, The Reach hopes to continue these endeavours, ensuring this important moment in our history will regain its rightful place in the collective memory of generations to come.

The Reach Gallery Museum and its partners are grateful to have been recognized with the Award of Merit for Excellence in Community Engagement by the BC Museums Association for Semá:th Xó:tsa: Sts’ólemeqwelh Sxó:tsa, its accompanying performance, Luminous Waters, and related educational resources.