Book Review and Author Conversation

Grace Eiko Thomson with Lindsay Foreman, Roundup Managing Editor

Chiru Sakura, Falling Cherry Blossoms: A Mother & Daughter’s Journey through Racism, Internment, and Oppression

By Grace Eiko Thomson

Published by Caitlin Press Inc., Winter 2021

Grace Eiko Thomson, 2010s.

Photo credit: John Endo Greenaway.

Are you looking for an emotionally honest, multi-generational story that describes the hardships endured by individuals and families of Japanese ancestry within the lands known today as Canada? Chiru Sakura, Falling Cherry Blossoms, is a memoir that details over 100 years of experiences shared by Sawae Nishikihama and her daughter Grace Eiko Nishikihama Thomson between 1913 and the present day. Sawae and her husband Torasaburo immigrated to Canada in 1930 to build a better life for their family. World politics, colonial policies, and societal expectations erected many barriers for the Nishikihama family, many of which still remain today. As the recent discoveries at former Residential School sites have invoked, we must all work together to build a more empathetic, inclusive, and equitable country for current and future generations.

This memoir interweaves the experiences of Sawae and Grace as their relationship is strengthened over the course of their lives. The lack of understanding and frustration felt at times between both women is palpable by the reader, but the love that they shared and the respect that they had for one another was ever-present. Strength, resilience, determination, and patience characterize both of these hardworking women as they share their individual and family experiences in Japan, Steveston, Paueru Gai (Powell Street in Vancouver), Minto Mines, Middlechurch, Whitemouth, Winnipeg, Fort Garry, Vancouver, Nunavut, Leeds, Prince Albert, and Burnaby.

The Nishikihama family’s culture and language is peppered throughout the memoir. We learn key Japanese terms such as hakujin (White people), chadō (tea ceremony), ikebana (flower arrangement), niisan (older brother), Nisei (a person born in Canada whose parents were immigrants from Japan), Issei (first-generation Japanese to immigrate to Canada), and odori (Japanese dance). We read about the language barriers faced by Sawae as she raised her family and the high expectations she held for her second daughter Grace, upon whom she greatly depended to adapt to the changing world around her. Sawae and Grace share about the strong family and community bonds they developed and the support they gave to other family members in B.C., Canada, and Japan.

From an early age Grace recalls the everyday art that her mother incorporated into their lives: “[art] had always been present in my life, except that it had not been called art, per se, but was merely accepted as a way of life.” Grace is fluent in Japanese, both spoken and written (including calligraphy), learned from her mother in after school lessons. She appreciated the language, music, poetry, and her mother’s skills as a seamstress that ensured the perpetuation of Japanese culture and a continued avant-garde Canadian style. Perhaps this ambient culture led to Grace’s chosen career as a curator in both gallery and museum settings.

Grace shared that:

In the process of translating my mother’s memoir, I realized there was a generational difference in how we viewed things. I was always beside my mother, helping her – I never had a childhood. I had two brothers and a baby sister – of course my mother needed me. I was raised by my mother not by Canadian culture. It was a difficult childhood.

My mother chose me to learn Japanese culture and language. It might have been different if my older sister was with us in Canada and not in Japan with our grandmother (i.e., my father’s adoptive mother). Today I can say I was privileged learning from my mother. Even though she was so strict at the time and I just wanted to play outside with my friends.

Visitor and Community Engagement,

Professional Specialization Certificate

Connecting people, communities and culture.

This 4-course micro-credential brings focus and increased understanding to the skills and strategies needed to build and maintain relationships with diverse communities so organizations can better engage and serve their public(s).

Roundup Managing Editor Lindsay Foreman had the opportunity to speak with Grace about her life experiences and the composition of Chiru Sakura, Falling Cherry Blossoms.

LF: Are you able to share about your professional background and what drew you to a career in the arts, culture, and museum sector?

GT: As a daughter of Japanese immigrants, my childhood was raised in/with Japanese culture, which is largely based on art, that is the choices we make each step of the way in both mental and physical responses to things and events around us. Also, in my case, always influenced by Mother, watching her writing (to discover later that it was a diary that she kept throughout her lifetime), poetry (citing adages), and practising of calligraphy (an art form in itself), but as well, flowers she arranged, or books she read, and the pride she took in designing and sewing.

Also, watching father always enjoying cooking when he had the time, and on Sunday mornings making us pancakes for breakfast, as a special event. I never connected these activities, as a child, to art, per se, but as part of a normal life, simply as a way of life.

Then, beginning with the church basement gathering (in Winnipeg) of amateur artists, my first experience of making art with others, discovering a way to express who I am through drawings, paintings, and constructing objects.

LF: Your artistic and curatorial studies led you to work closely with various ‘marginal’ Canadian communities (e.g., Indigenous, Japanese) from very early on in your career. Are you able to share about your artistic and curatorial practises and how you have/continue to work in an inclusive and holistic manner?

GT: I discovered that I was living a very self-centred life, always dealing with issues of racism, until I realized other groups, here in Canada, had similar experiences. So I began to reach out to them through my work as a curator, to interact and to learn about experiences of ‘others’ (i.e., Indigenous, Inuit). I had little if any contact with the Black or Chinese communities during these years in Winnipeg.

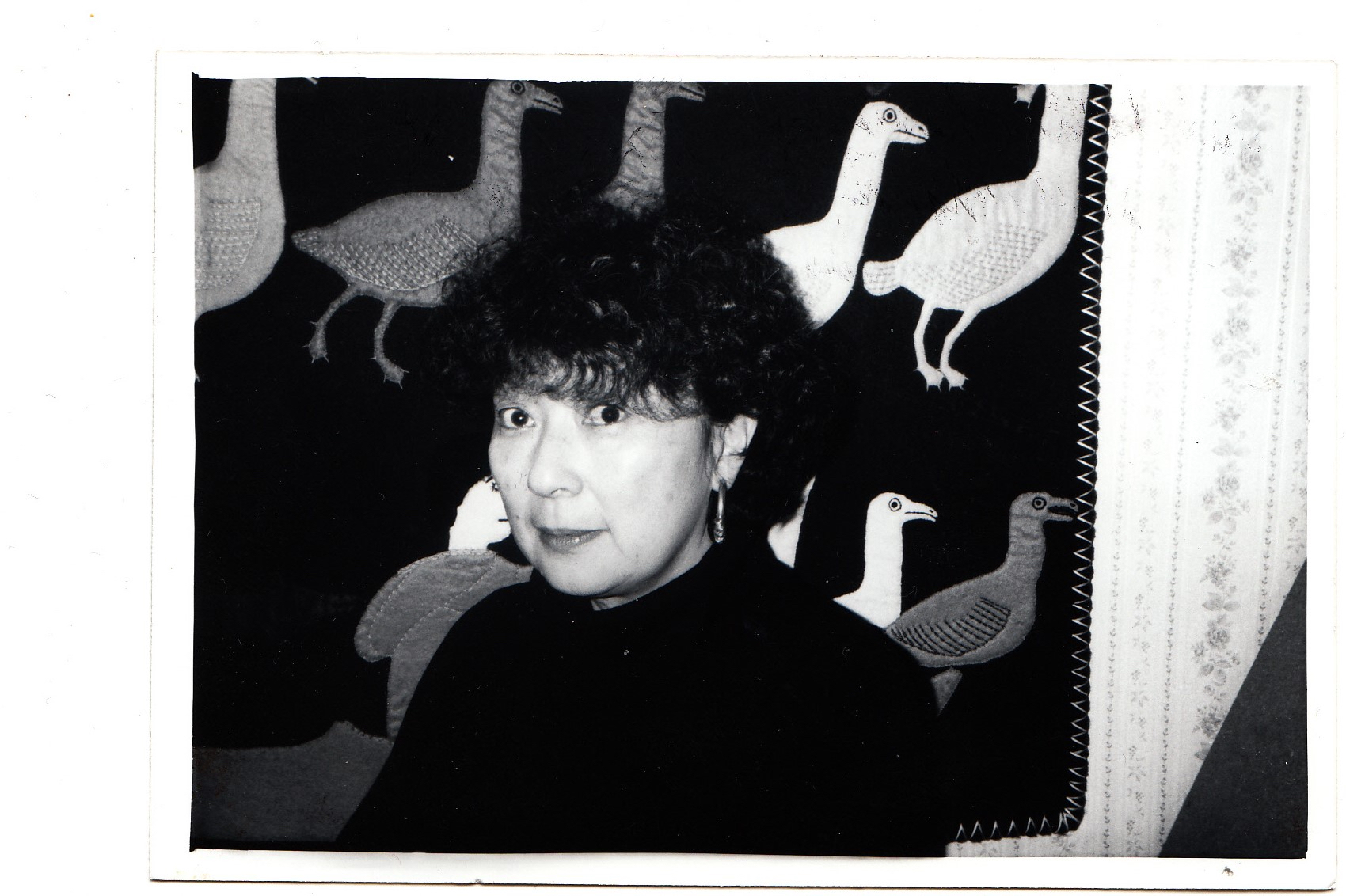

While at Sanavik Cooperative in Baker Lake, Nunavut, I worked to choose the images from drawings by Inuit artists to be turned into prints and included in the annual print collection marketed in the south. I learned that this process was controlled by the Eskimo Arts Council, not by the Inuit artists and their community members who produced the work.

While in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, I worked to bring local and provincial Indigenous artists together to take part in the Little Gallery’s programs. This was the first time that I identified “selective exclusion” practices in galleries. Although Indigenous artists were producing artwork in the area, the artists and their work were not included in the local gallery exhibition programs.

Through this experience of cross-cultural appreciation and sharing, when next working with the Burnaby Art Gallery, I proposed exhibitions that focused on cross-cultural artists’ works (i.e., Cultural Migrations and Difference). Tracing Cultures I, II, III and IV excluded no one’s work from the exhibition programs. During this time, I also curated artworks by Natalka Husar, an artist of Ukrainian descent and history, which exposed other (i.e., Ukrainian, Eastern European) experiences of discrimination. In such ways, I was able to resolve the personal experiences of racism, as a Japanese Canadian, realizing that many others had walked the path I had tread (i.e., Indigenous, Eastern European, in particular).

Grace Eiko Thomson with wall hanging by Janet Kugusiuq of Baker Lake, Nunavut, 1980s.

Photo credit: Grace Eiko Thomson.

LF: In Chiru Sakura, you shared many incidents of unfair, and often inappropriate interactions with different men from your childhood, right through to your curatorial/Executive Director work in the 2000s. Do you have any advice for young professionals who continue to face similar challenges?

GT: Writing this story began as an effort to share, originally with my two sons and family members, about their family background… particularly my parents’ history of struggles, as related to Canada’s not so distant past racist history.

I feel grateful that Caitlin Press offered me the chance to share more widely, the life I shared with my parents, as related to racism that existed openly and normally, supported by the governments of Canada, and the sexism that I, as a girl and as a woman experienced (not unknown to our world, though largely hidden by those in power, the majority of whom are male).

In writing this story, I had begun with the main topic of being a person of Japanese ancestry, struggling with memories of how my parents and siblings were treated. We were always looked upon (negatively) as ‘different’, confirmed by the Canadian government during the Second World War, even as my parents were naturalized Canadians, and me, a Canadian born.

During the process of writing my experiences from childhood to becoming an employee in various offices, then into university studies toward a professional career (i.e., artist, curator, historian), and as a mother of two sons, products of an intermarriage, what became evident in my life story went beyond racism. Issues of sexism were revealed, as I was always seen (negatively) as an ‘Asian’ girl, woman, mother, or academic, not a ‘Canadian.’ If I was viewed positively, it was as an ‘exotic’ creature.

I knew that during their childhood, my sons were well aware of their mother’s ‘difference’ as observed through the eyes of those around them (both fellow students and their parents), especially when we were seen together. While I participated and even led some community and school committee groups to show that I was one of ‘them’, though often insulted, I regret that I did not remain to do more instead of feeling hopeless and leaving. I did not share such experiences with my husband.

Regretfully, I did not have the courage or ability to face these challenges, which led to my disappearance from my sons’ daily lives when they were well into their teens, the older already in university. I felt they were better off to be raised by their father, without their mother’s ever-presence, as I went out to find myself. In order to benefit them, I had to continue my own journey.

Racism was and continues to be accepted as the norm. Although felt and endured by many, racism continues to be an advantage of those holding power in our society (i.e., white, men).

And so, the writing of this book, which began as a way to share family history with my children, gave me the opportunity to share Canada’s racist history with younger generations. It is important to be aware of this past and to be vigilant in preserving justice for all into the future. You have to put effort into exposing injustices and get support to do that. Fight it to the end. Don’t quit and allow it to continue.

LF: Your advocacy for social justice started at a very early age. You were the first female President of the Manitoba Japanese Canadian Citizens’ Association in 1955. You questioned the processes of the Eskimo Arts Council in the 1980s. You were the first Executive Director/Curator of the Japanese Canadian National Museum in the 2000s. You were also the President of the National Association of Japanese Canadians in the 2000s. And you continue to push boundaries to eliminate social injustices within Vancouver, B.C., and Canada. What drives you to continue this work?

GT: It is not a matter of being driven… when something that bothers me or reminds me of the past appears before me, I naturally get interested… and too often get involved.

While I had a very strong mother, who married my father, a stranger, introduced to her by parents (an arranged marriage, which was normal in those days), and who immigrated to Canada in 1930, and settled happily in Vancouver, with dreams of a bright future, within a dozen years, in 1942, their lives, their hopes, and dreams were totally destroyed, never to be revived again. From 1942 until 1950, they lived under government restrictions, and even as they settled (finally as Canadian citizens) in Winnipeg in 1950, it was a major effort to raise their five children. The years of injustice that my parents and siblings endured, remain with me to this day.

Especially at this time, I am reminded of the fact that racism cannot be erased without major efforts from each of us. We must take leadership roles (not accepting ourselves as victims) in protecting the younger generations and our seniors. I am now 87 years of age… turning 88 in October, and the daily news doesn’t offer me much hope of change even as much has changed over my lifetime.